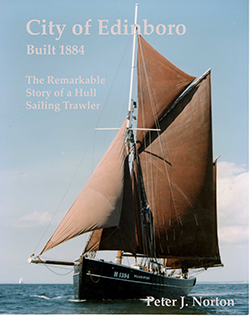

The Norfolk & Suffolk Boating Association Ltd (NSBA) hosted a Fundraising Supper recently to help to fund the restoration of one of the last remaining East Coast sailing smacks, the City of Edinboro, built in Hull 1884 by William McCann and now owned by the Excelsior Trust who owns and operates the Lowestoft sailing smack, the Excelsior, as a sail training vessel.

The Trust rebuilt the Lowestoft smack 35 years ago, and they now have exciting plans to develop their shipyard at Oulton Broad as a maritime heritage skills centre. Part of the development will be wooden shipbuilding, and it is proposed to use City of Edinboro as a vehicle for instruction. She has had a slipway built for her and lies in a dedicated temporary building.

The NSBA got involved in supporting this very worthwhile project for several reasons including the fact that one of the NSBA’s affiliated Clubs is the Merchant Navy Assn Boat Club whose Commodore, Ian Pearson, happens to live in Hull and is involved in the project to restore the City of Edinboro.

The fundraising supper, held in Horning Village Hall, was fully subscribed and attracted over 50 people. Not only was there a very enjoyable supper, but there was a charity auction, including local artworks, a raffle and the sale of books about the City of Edinboro signed by the author, Peter Norton.

The fundraising supper, held in Horning Village Hall, was fully subscribed and attracted over 50 people. Not only was there a very enjoyable supper, but there was a charity auction, including local artworks, a raffle and the sale of books about the City of Edinboro signed by the author, Peter Norton.

The presentation, by the locally very well-known Jamie Campbell who is Chairman of the Trustees of the Excelsior Trust was fascinating and included the history of the 76-foot-long City of Edinboro herself but also provided an interesting insight to the work of these large East Coast sailing trawlers which operated as far away as The Faeroes and Iceland in the nineteenth century long before many of them from about 1890 onwards, were sold and converted to steam, but City of Edinboro continued to operate under sail alone until 1924 when she was fitted with a small auxiliary engine, although she continue to operate as a gaff-rigged ketch.

During his presentation Jamie told us that Excelsior is not a viable business, the boat generates an operating loss every year. “If you think it through, a century-old, wooden hull – around 100 tons of oak with a full-time, qualified crew is unlikely to generate an operating profit – particularly when the customers are children with no money. Making up the shortfall with fund raising activity is where the rest of us come in – which is why we are a charity.

During his presentation Jamie told us that Excelsior is not a viable business, the boat generates an operating loss every year. “If you think it through, a century-old, wooden hull – around 100 tons of oak with a full-time, qualified crew is unlikely to generate an operating profit – particularly when the customers are children with no money. Making up the shortfall with fund raising activity is where the rest of us come in – which is why we are a charity.

“The Excelsior Trust was established in 1982, and Excelsior was completed by 1990. Despite the odds, we are still here and over the years we have taken around 11,000, often disadvantaged children to sea. What I am trying to say is that there is no crock of gold. There are no borrowings, but we must raise the money to do what we want to.”